Between 2.7 million and 3.9 million Americans have hepatitis C, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The virus can remain dormant for years, and by the time symptoms arise, the organs may already be damaged. Except for flu, hepatitis C takes more lives than all other CDC-tracked infectious diseases combined — and that includes HIV, tuberculosis and other more prominent diseases. In 2015, 19,629 Americans died from hepatitis C, mostly from liver disease caused by the virus.

For years the few treatments for hepatitis C had severe side effects and were not very effective at eliminating the virus from the body. But a new generation of powerful drugs came out in late 2013. These drugs have minimal side effects and usually require taking just one pill a day for two to three months. The cure rate is more than 90 percent.

Given this powerful new option, it’s possible to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health threat in the U.S. by 2030, researchers say. But social and financial barriers remain, so it would take a concerted effort by government, health plans, doctors and hospitals.

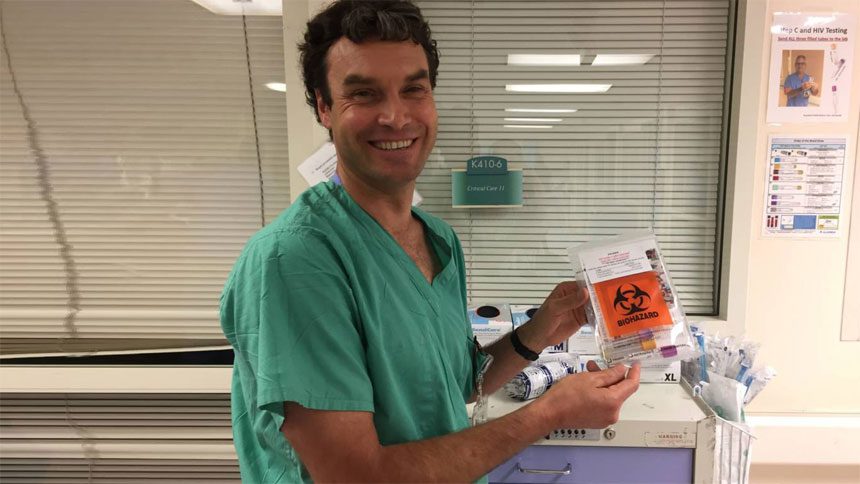

Dr. White hopes Highland Hospital can be a leader in the fight, and a model for other hospitals tackling the hepatitis C epidemic.

“Hepatitis C has gone from a disease that I had no incentive to look for to diagnose, because I couldn’t do anything about it, to essentially a curable disease with treatment that’s well tolerated,” White said.

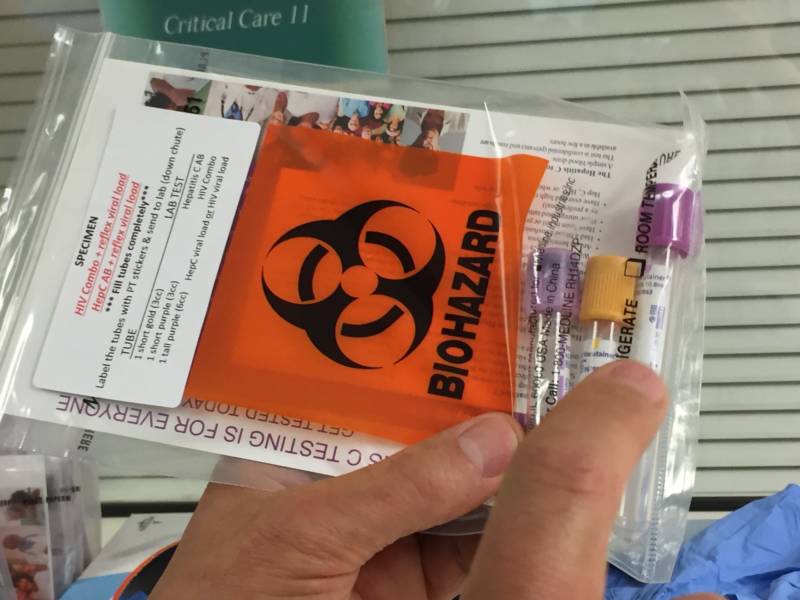

Highland staffers test nearly everyone who comes to the ER and gets blood drawn. They’ve built a robust electronic medical system that reminds medical staff to test for hepatitis C when doing other blood tests, as long as the patient hasn’t had this test in the past year. Highland was one of the first ERs to test for hepatitis C like this nationwide. That helps flag infections among low-income or undocumented patients who use the ER for primary care.

And the work doesn’t end in the ER. If patients test positive, they get a call or visit from Mae Petti.

Petti has a desk a few floors above the emergency room. She spends hours making phone call after phone call. In her friendly, polite but insistent manner, she persists until she speaks with every patient on her list. As Highland’s hepatitis C linkage coordinator, Petti will contact patients again and again until they come in to get follow-up care.

Few hospitals have someone like Petti — her position at Highland is grant-funded. And her work is paying off: Highland has doubled the number of people who return for follow-up appointments. Now, patients can start getting treated for hepatitis C in as soon as two weeks. Previously, it took six months after a positive test before a patient began treatment.

San Francisco’s Mission to Stamp out the Virus

Across the bay, San Francisco has its own approach to the problem. A group there has been addressing hepatitis C since former Mayor Gavin Newsom assigned a specific task force to the issue in 2009. The group’s mission was first to recommend how the city should address hepatitis C. These days, they believe the threat of hepatitis C can be stamped out, and they think San Francisco is the place to do it.

At a recent task force gathering at San Francisco’s Department of Public Health, doctors, public health workers and many former hepatitis C patients — now cured — took their seats around a table.

After a dinner of pizza and salad, San Francisco’s viral hepatitis coordinator, Katie Burk, launched into a presentation. She listed reasons why she thinks San Francisco is a great candidate for elimination. First, she said, the city of San Francisco is small.

“That matters when you’re trying to grab folks from all parts of the city, and make sure they’re getting the care they need,” Burk said.

And there’s a historical commitment to fighting disease here.

“We have this really incredible HIV program infrastructure in San Francisco,” she said. “We’ve built a lot of what we’ve done with hepatitis C sort of on the back of that program, and learned from a lot of our successes and challenges.”

Hepatitis C is transmitted by blood — and these days most of that happens through shared needles. Stopping the spread of the virus is therefore inextricably connected with efforts to end addiction to injectable drugs. San Francisco has places to exchange dirty syringes for clean ones, and plenty of programs and clinics offer “medication-assisted treatment” — usually using buprenorphine, which helps people addicted to heroin and other opioids kick the habit.

San Francisco has another weapon too: a coalition specifically devoted to hepatitis C elimination, called End Hep C SF. It launched in 2016.

The End Hep C SF coalition has created something that experts consider crucial for the elimination of hepatitis C: an accurate estimate of how many residents harbor the virus, whether they are aware of it or not. In San Francisco, the current estimate is 12,000 people.

It’s unusual for a city to have a number like that to work with, because typically public health departments know only the number of people who have recently tested positive for hepatitis C. But San Francisco officials have gone farther: subtracting estimates of people who have been cured, died or moved away. They have calculated how many people probably have the virus, but have yet to be diagnosed.

Having that estimate is exciting, according to public health consultant Shelley Facente, who was also at the meeting, because it will allow the city to set goals of how many people to treat each year, and can offer an idea of when hepatitis C can largely be wiped out. The data have also helped identify target groups that have disproportionately high rates of hepatitis C in San Francisco, like transgender women.

Facente said roughly 4,500 San Franciscans already have been cured, using the new class of treatments for hepatitis C.

“That means this is doable,” Facente said, referring to elimination. “We can really make this happen. It’s very exciting that we’ve already made such progress. And now that we have even more information about what we need to do and where we need to go, it’s even going to get better from here.”

Remaining Barriers to Elimination

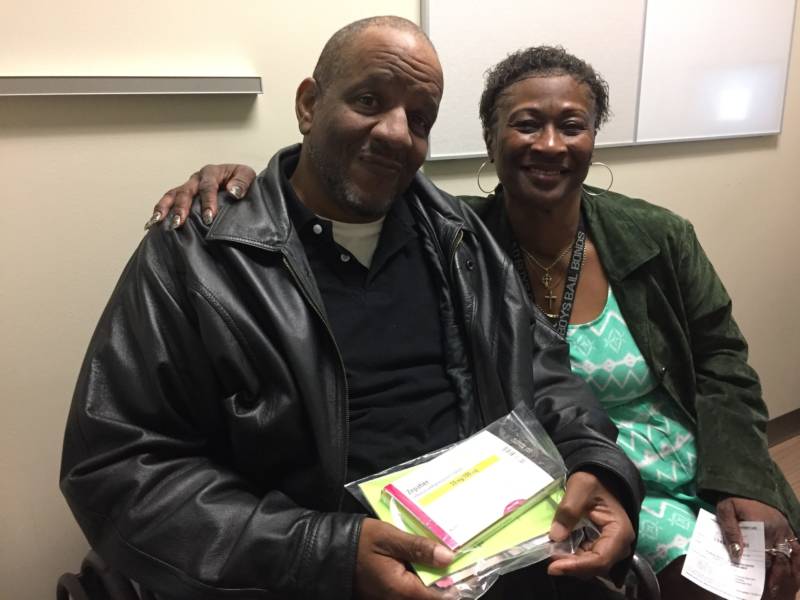

Back at Highland Hospital, patient June Bullock had an appointment to pick up a refill of pills for his hepatitis C treatment. He met with physician assistant Amy Smith, who guides Highland patients through the treatment. Smith handed Bullock his last pack of pills and asked if he had any questions. His wife, Alfreda, was the one who spoke up.

“My daughter says nobody can drink behind him out of a straw,” Alfreda Bullock said.

“No,” Smith replied. “That’s not true.”

“There’s a whole bunch of stuff going on, you know what I’m saying?” Bullock said, explaining she’d heard a lot of misinformation about the virus.

Smith took the blame. “Yeah. Well, I’m sorry we haven’t covered that.” Smith then reviewed for them how hepatitis C is spread.

Research shows that to really curb hepatitis C, it takes a program like Highland’s: test widely, and then treat aggressively.

But, new hepatitis C infections still increased in California by 5.5 percent between 2011 and 2015, according to the state Department of Public Health.

That’s frustrating for people like Smith, who has seen many people get cured.

“There are a lot of good people out there doing good work,” she said. “I just don’t think all the pieces are in place just yet.”

Unaffordable drugs, for instance, are still one of the biggest barriers to treatment, Smith said.

The cheapest available drug retails at about $26,000 for a course that ranges from two to four months. Others can cost as much as $133,400. While insurance companies often negotiate lower prices, some have still tried to control costs by instituting limits on who qualifies for treatment.

Another problem is the nationwide opioid epidemic, which includes heroin abuse, often via needle. Many experts say that’s why hepatitis C infections are rising among people under 30 — although hepatitis C has traditionally been considered a disease of the baby boomers. This older generation grew up before the virus was identified, let alone subject to screening in the blood supply.

Some advocates say the fight against hepatitis C is especially difficult because society places little value on the lives of the people who tend to get the virus — current or former drug users, jail inmates and former prisoners.

Despite the challenges, efforts in the Bay Area show progress is still possible. The hope is that if a city like San Francisco can eliminate hepatitis C, others will follow suit.

https://www.kqed.org/stateofhealth/362025/theres-a-cure-for-hepatitis-c-why-are-so-many-people-still-dying-from-it